How to protect ourselves from

the dangers of artificial intelligence

© shutterstock

Why we need an ethics code to protect our human rights from AI

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has the potential to transform the advancement of humankind on a scale not seen since the Industrial Revolution. However, it also has the potential to create a myriad of ethical and legal problems. The classical example that combines both issues is the self-driving car. Imagine that such a vehicle is about to crash into a crowd of pedestrians. Should we have programmed the car’s software to protect the passengers or the crowd? What if there is just one bystander in danger compared with four passengers in the car? And what about legal liability when things go wrong? Who takes responsibility when a software bug results in a mis-manoeuvre that leads to the death or injury of passengers or passers-by?

AI is already being used in justice and law enforcement systems. The Metropolitan Police in London are experimenting with an automated facial recognition system (AFR) which they use at public events such as pop concerts, festivals and football matches. Mobile CCTV cameras scan crowds, seeking to match images of faces to mugshots of wanted criminals. According to data obtained using Freedom of Information laws, 98 per cent of such matches are false. The pressure group Big Brother Watch warns that automated facial recognition risks turning public spaces into biometric check points, with a potentially chilling effect on a free society, as people avoid joining protest marches for fear of being wrongly identified as criminals, and arrested and held in detention while checks on their identity are carried out.

Closer to home, researchers at University College London made an amazing discovery when processing data relating to 584 cases that went before our own European Court of Human Rights here in Strasbourg. An Artificial Intelligence “judge” was able to analyse existing case law and deliver the same verdict as the human ECHR judges in 79 per cent of the cases. The study found that ECHR judgments depended in reality more on non-legal facts relating to torture, privacy, fair trials and degrading treatment, than on legal arguments.

© Georg Stawa - President of CEPEJ

A wider issue concerns the collection of big data – for AI to progress, the quantity of data needed to achieve success will inevitably increase. This means that there will be ever higher risks for people’s data to be collected, stored and manipulated without their consent or even their knowledge. The recent scandal concerning Cambridge Analytica is a good example of this.

And what about cultural and political biases between individuals and countries? For example, in one culture it may be deemed acceptable to take a photo of a person, but another may forbid photos to be taken for religious reasons. AI programmes may also incorporate the prejudices of their programmers and the humans they interact with. A Microsoft AI chatbot called Tay became racist, sexist and anti-Semitic within 24 hours of interactive learning with its human audience. Another software (COMPAS), which was developed to help US courts predict the odds of defendants re-offending, was found to be biased against African-Americans.

According to Paul Nemitz, a leading architect of the European Union’s new law on data protection (GDPR), “We need a new culture of technology and business development for the age of AI which we call ‘rule of law, democracy and human rights by design’. These core standards should be baked into AI because we are entering “a world in which technologies like AI become all pervasive”.

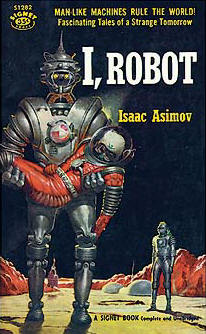

© Wikipedia

In his 1942 short story “Runaround”, the American science fiction writer Isaac Asimov elaborated what he called the Three Laws of Robotics, to govern relations between humans and robots:

First Law - A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

Second Law - A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

Third Law - A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.

Many experts now believe we need a similarly clear and comprehensive set of principles to protect humankind from potential abuses of AI. With this aim in mind, our European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) has adopted the first European text setting out ethical principles relating to the use of AI in judicial systems. These include compatibility with fundamental rights, non-discrimination, maintaining quality and security, acting transparently, impartially and fairly and finally ensuring that users of AI are informed actors, in control of their choices.

© Stéphane Leyenberger - CEPEJ

Brought together in a European Ethical Charter, the principles provide a framework to guide policy makers, legislators and justice professionals when grappling with the rapid development of AI in national judicial processes. The CEPEJ, and its Council of Europe « mother ship » believe it is essential to ensure that AI remains a tool in the service of the general interest, always respecting individual rights. The intelligence may be artificial, but the dangers it poses to our freedom are very real.