Free expression and

media under threat

Unwarranted interference, fear, self-censorship

Journalists under pressure

Protection of journalists in Europe

Interview with Professor Marilyn Clark

Journalists are often exposed to violence,

threats and self-censorship in Europe

A survey based on a sample of 940 journalists reporting from the 47 Council of Europe member states and Belarus, shows that journalists in Europe are often exposed to serious unwarranted interference – including violence, fear and self-censorship.

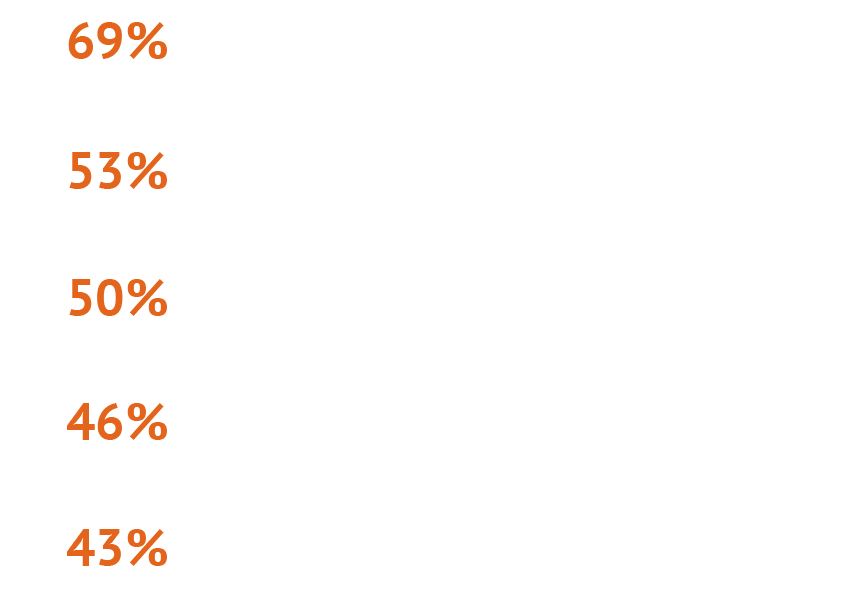

Nearly a third of respondents (31%) had experienced physical assault over a period of three years. The most common interference, reported by 69% of the journalists, was psychological violence, including humiliation, intimidation, threats, slandering and smear campaigns. The second most common interference was cyberbullying, reported by 53%, mostly in the form of accusations of being partisan, personal attacks, public defamation and smear campaigns. Reports of intimidation from interest groups were the third most frequent interference mentioned (50%), followed by threats with force (46%), intimidation by political groups (43%), targeted surveillance (39%) and intimidation by the police (35%).

The study was commissioned by the Council of Europe, and carried out by experts Marilyn Clark and Anna Grech, from the University of Malta, with the support of the Association of European Journalists, the European Federation of Journalists, Index on Censorship, the International News Safety Institute and Reporters without Borders.

The survey was carried out between April and July 2016 via an anonymous online questionnaire in five languages among journalists mainly recruited from members of five major journalists´ and freedom of expression organisations. It aims to contribute evidence-based data to the debate on how to address threats to media freedom, which have experienced a significant increase in Europe in recent years.

Safety of journalists platform The survey on the online bookshop

Experiences of unwarranted interference in last 3 years

Protect journalists - protect democracy!

How resilient are Europe’s democracies?

Since the Second World War, Europe has come to understand that democracy is by definition pluralist and that giving citizens the right to be different and to criticise authority makes our countries more stable, not less.

Millions of Europeans continue to exercise their civil liberties, participate in elections, practise free speech and enjoy the benefits of living in societies governed by the rule of law. But many of our societies appear less protective of their pluralism and more accepting of populists who invoke the proclaimed will of “the people” in order to stifle opposition and dismantle the checks and balances that stand in their way.

Most concerning are the instances of governments openly challenging constitutional constraints and disregarding their international obligations to uphold human rights. Attempts are made to justify such actions on the basis that they serve the majority population. Those who oppose them are discredited and undermined, including political opponents, journalists and judges.

How strong are Europe’s checks and balances when it comes to populism?

As nationalist and xenophobic parties make gains in a growing number of countries challenging elites and exploiting public anxieties over migration, Secretary General Thorbjørn Jagland, in his 2017 report on the state of human rights, democracy and the rule of law, invites Council of Europe member states to take a serious look in the mirror and take the lead in building trusted institutions and inclusive societies able to withstand populist assaults.

We cannot blame our populist problems exclusively on the most incendiary leaders or parties, nor simply on the rise of fake news. Their actions are deeply irresponsible and it is true that many exploit the internet to spread misinformation. But they thrive most easily where people have lost trust in their governments, parliaments and courts; where critical journalism and NGOs already struggle to be heard; where minorities have not been integrated into wider society; and where large numbers of citizens feel deprived of opportunities.

What is a good way of telling if a democracy is healthy?

Populism

Interview with Jan-Werner Müller

What is Populism?

Populism has become a fashionable term. It is increasingly used as a catch-all label for political forces and events which challenge the status quo, and as an insult to discredit a wide range of political actors. This overuse is problematic: using populism too widely dilutes its meaning, making it difficult to identify the real populist threat facing our democracies.

It is important to be precise about what does and does not constitute populism.

While it has many different forms, populist acts, individuals and movements display some common characteristics. They tend to be anti-establishment, respond to widespread public grievances and appeal to emotions. So, however, do most politicians.

Real populism goes one step further: invoking the will of “the people” in order to put itself above democratic institutions and overcome obstacles which stand in its way. The people are presented as a single, monolithic entity with one coherent view. By claiming exclusive moral authority to act on their behalf, populism seeks to delegitimise all other opposition and courses of action. All actions are justified on the basis of this exclusive moral authority.

Populism damages democracy by:

- limiting debate, delegitimising dissent and reducing political pluralism;

- dismantling democratic checks and balances, including the rule of law, parliamentary authority, free media and civil society;

- undermining individual human rights and minority protection;

- challenging international checks on unrestrained state power.

The resurgence of populist politics is a particularly worrying development in Europe, given the historical context. Since the middle of the 20th century it has become broadly accepted that constitutional and parliamentary democratic systems are necessary to restrain the notion of absolute sovereignty of the people. The consensus has been that pluralism, inclusive debate and the protection of minority interests against aggressive majoritarianism are essential for maintaining stable societies and democratic security.

#stand4democracy – Populism

Is populism a threat to democracy in Europe? What is it, and what do our societies need to do about it?

The dangers of Populism

Populism erodes free speech

Populist movements benefit from their democratic right to express themselves freely, even when the views expressed are controversial and provocative. However, the populist approach to free speech is ungenerous and discriminatory. Critics of the populist cause and unsympathetic media are dismissed as inaccurate, biased and self-serving. In this way, populism eliminates dissent and erodes a fundamental principle in any democracy: our right to disagree. While successful populism tends to rely on established media outlets lending their approval to its aims, the internet has also created unprecedented opportunities to build support. Social networks in particular allow populist narratives, fake news and “alternative facts” to spread with lightning speed, often unchallenged and uncorrected.

Trust

The “fake news” phenomenon

Fake news is a symptom of citizen’s serious lack of trust in the media. There is a decline in independent, accurate and professional journalism as traditional media lose funding and leverage, and social media increasingly become the main distributors of news.

False information, rumours and propaganda have always existed and have always been particularly prevalent in politically charged times, such as before elections. However, today such information can be rapidly produced and disseminated on the internet, in particular via social media platforms, usually without prior verification of accuracy or correctness and without editorial control. Sources are often anonymous and distribution is automatic, including through social bots that are used to “like” and spread misinformation, while appearing to represent real people.

Both traditional media and social media have reacted with a high degree of responsibility in the face of concerns expressed about false information. Several media organisations have strengthened their fact-checking capabilities while some social media have stepped up their engagement in designing and deploying tools that enable users to flag possible false stories which are then examined for their accuracy by third-party fact-checking organisations.

Any response to the challenge of false information must address the root causes of the problem rather than its symptoms, and must be carefully balanced to not affect the legitimate exercise of human rights and democratic participation.

The benefits of quality journalism

A well–functioning democracy requires free and diverse news media capable of keeping people informed, holding powerful actors to account, and enabling public discussion of public affairs. Existing research suggests that quality journalism can increase levels of political knowledge, participation, and engagement and can furthermore help reduce corruption and encourage elected officials to represent their constituents more effectively. The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism has reviewed the challenges and opportunities for news media and journalism in today’s changing media environment.

A well–functioning democracy requires free and diverse news media capable of keeping people informed, holding powerful actors to account, and enabling public discussion of public affairs. Existing research suggests that quality journalism can increase levels of political knowledge, participation, and engagement and can furthermore help reduce corruption and encourage elected officials to represent their constituents more effectively. The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism has reviewed the challenges and opportunities for news media and journalism in today’s changing media environment.

4

actions

to contribute

2

Inscrivez-vous à la newsletter et restés informés

3

Add a link on your website